Nonfiction

eBook

Details

PUBLISHED

Made available through hoopla

DESCRIPTION

1 online resource

ISBN/ISSN

LANGUAGE

NOTES

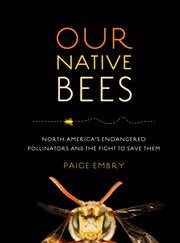

A New York Times 2018 Holiday Gift Selection Honey bees get all the press, but the fascinating story of North America's native bees-endangered species essential to our ecosystems and food supplies-is just as crucial. Through interviews with farmers, gardeners, scientists, and bee experts, Our Native Bees explores the importance of native bees and focuses on why they play a key role in gardening and agriculture. The people and stories are compelling: Paige Embry goes on a bee hunt with the world expert on the likely extinct Franklin's bumble bee, raises blue orchard bees in her refrigerator, and learns about an organization that turns the out-of-play areas in golf courses into pollinator habitats. Our Native Bees is a fascinating, must-read for fans of natural history and science and anyone curious about bees. Our Native Bees is the result of Paige Embry's yearlong quest to learn more about the forgotten, yet fundamental, native bees of North America. Paige Embry has a BS in geology from Duke University and an MS in geology from the University of Montana. She has worked as an environmental consultant, taught horticulture and geology classes, and run a garden design and coaching business. She has written articles for Horticulture, The American Gardener, and other magazines. Visit her at paigeembry.com. Introduction Native bees are the poor stepchildren of the bee world. Honey bees get all the press-the books, the movie deals-and they aren't even from around here, coming over from Europe with the early colonists. In 2015, when President Barack Obama's White House issued a plan to restore 7 million acres of land for pollinators and more than double the research budget for them, it was called the National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators. Four thousand species of native bees, not to mention certain birds, bats, flies, wasps, beetles, moths, and butterflies, reduced to "other pollinators." Sigh. Honey bees are fine bees. They dance and make honey and can be carted around by the thousands in convenient boxes, but from a pollination point of view, they aren't super-bees. On cool, cloudy days when honey bees are home shivering in their hives, many of our native bees are out working over the flowers. Bumble bees do their special buzz pollination of tomatoes, blueberries, and various wild species. Squash bees wake up early to catch the big yellow squash blossoms while they're open. The trusty orchard mason bees are such hard-working yet slovenly little pollen collectors that several hundred can pollinate an acre of apples that requires thousands of honey bees. Where are the book and movie deals for these bees? Well, I'm making a small start for them here. My obsession with bees began because of tomatoes, a plant with roots deep in my Georgia childhood. The summertime table in my house always had a plate of sliced tomatoes on it. My dad grew tomatoes wherever he could: along a brick wall at one house, in the only sunny spot by some azaleas at another, in a tiny plot of red dirt outside his office door for a while. When I grew up and moved away, I, too, grew tomatoes, although with varying success in the cool summers of Seattle. Tomatoes have been a fixture in my life. Now, tomatoes have some flexibility in their pollination requirements. Some pollination happens as a result of wind just shaking the plants, but more and bigger tomatoes result with the help of bees. Not just any bee can do it, though. It wasn't until I was nearly fifty that I learned that honey bees can't produce those tasty red and orange globes. Tomatoes require a special kind of pollination called buzz pollination, where a bee holds onto a flower and vibrates certain muscles that shake the pollen right out of the plant. Honey bees don't know how to do it, but certain native bees

Mode of access: World Wide Web